More teenagers are struggling with body dissatisfaction than ever before, and the consequences extend far beyond typical adolescent insecurity. Body image concerns during the teenage years can fuel serious mental health issues including depression, anxiety, and eating disorders that persist well into adulthood.

For parents, watching their children internalize harsh judgments about their bodies and withdraw from activities they once enjoyed is both heartbreaking and alarming. Understanding what’s driving this trend and knowing how to intervene effectively has become essential for protecting teenagers during these vulnerable years.

Why Teenagers Are Particularly Vulnerable

The adolescent brain is still under construction, particularly in regions responsible for emotional regulation and social processing. This means teenagers experience heightened sensitivity to social feedback, real or perceived. A passing comment about appearance can lodge itself in memory and replay endlessly. An offhand comparison can become internalized as a fundamental truth about their worth.

Social media amplifies all of this exponentially. Today’s teenagers aren’t just seeing idealized images in magazines they can put down or on TV shows they can turn off. They’re receiving constant streams of content algorithmically designed to draw their attention, often through harmful tactics like comparison and insecurity. They’re also creating content themselves, learning early that their value can be quantified in likes and comments and that their appearance is something to be packaged and evaluated by others.

What Unhealthy Body Image Looks Like

Unhealthy body image in teens is rarely loud or dramatic. More often, it unfolds quietly, in patterns that can be easy to dismiss as “normal teenage insecurity.” But when dissatisfaction with appearance becomes persistent, emotionally charged, or begins to shape daily choices, it signals something deeper than passing self-consciousness.

Below are some of the most common — and often overlooked — signs of genuine body dissatisfaction among teens. While no single behavior tells the whole story, clusters of these patterns deserve attention.

Common signs of unhealthy body image in adolescents include:

Persistent negative self-talk about appearance

Occasional complaints are common, but ongoing, harsh criticism of one’s body is not. This may include fixating on perceived flaws, rejecting compliments, or repeatedly asking for reassurance about weight, shape, or looks.

Interpreting neutral situations as appearance-based judgment

Teens may assume others are criticizing their body, reading social interactions, photos, or comments through a lens of shame or comparison.

Changes in eating behaviors or attitudes toward food

Body dissatisfaction doesn’t always show up as obvious restriction or bingeing. It can look like suddenly cutting out entire food groups, expressing anxiety around family meals, developing rigid “food rules,” or spending excessive time researching nutrition, calories, or “clean eating.”

Increased anxiety or control around eating situations

Avoiding shared meals, needing to eat alone, or showing distress when eating plans change can all signal deeper body-related fears rather than simple preferences.

Avoidance of activities that involve visibility or comparison

Teens may withdraw from swimming, sports, shopping for clothes, school events, or being photographed. This is a sign of deeper body image issues, especially if these were previously enjoyed activities.

Social withdrawal linked to appearance concerns

Pulling away from friends or declining invitations may stem from fear of being seen, judged, or compared rather than general social disinterest.

Compulsive or rigid exercise patterns

Exercise becomes concerning when it shifts from enjoyment to obligation. Warning signs include distress when unable to work out, prioritizing exercise over school or relationships, or continuing to exercise despite injury, illness, or exhaustion.

Mood changes tied to appearance + self-worth

Body dissatisfaction in teens is closely linked to depression and anxiety. When a teen’s sense of value rises and falls based on how they feel about their body, emotional stability often follows the same fragile pattern.

Unhealthy body image isn’t defined by one comment or behavior. It’s defined by persistence, rigidity, and the degree to which appearance begins to dictate a teen’s emotional well-being and daily life. Recognizing these patterns early creates space for support, intervention, and healing — before distress becomes entrenched.

How Parents Can Help

Well-meaning parents sometimes inadvertently reinforce the very messages they’re trying to protect their children from. Complimenting your daughter for looking thin or praising your son’s muscles might seem supportive, but it confirms to them that their bodies are constantly being evaluated and that appearance determines value.

Stop commenting on bodies entirely.

This includes your own body, other people’s bodies, and your teenager’s body. Compliments about appearance, even positive ones, teach teenagers that how they look matters more than who they are or what they do. Focus instead on character, actions, values, and capabilities.

Model a functional relationship with your own body.

If you constantly criticize your appearance, discuss dieting, or express guilt about eating certain foods, your teenager learns those patterns regardless of what you say directly to them. Demonstrate that bodies are tools for living, not flawed ornaments in constant need of improvement.

Develop media literacy as a family skill.

Teenagers need help understanding that social media platforms profit from insecurity, that images are routinely edited beyond recognition, and that the people they’re comparing themselves to are presenting carefully curated highlight reels. These conversations shouldn’t be lectures but ongoing discussions that build critical thinking skills.

Create an environment where food is neutral.

When families moralize eating by labeling foods as “good” or “bad,” assigning guilt to certain choices, or treating meals as opportunities for restriction, they lay the groundwork for disordered eating. Food provides nourishment and pleasure, and both experiences are part of a full, balanced life.

Know when professional help is necessary.

If body image concerns are interfering with your teenager’s ability to function socially, academically, or emotionally, don’t wait for things to improve on their own. Mental health professionals who specialize in adolescent body image and eating disorders can provide interventions that prevent dangerous patterns from becoming entrenched.

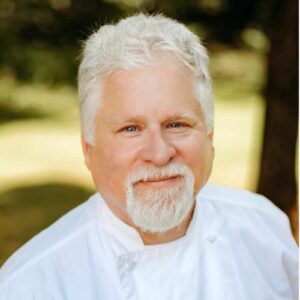

When Professional Treatment Makes All the Difference

For families navigating the difficult decision about professional treatment for body image issues or disordered eating, understanding what effective care looks like can provide clarity during a confusing time.

One parent whose daughter received treatment at Magnolia Creek shared: My daughter has been in residential treatment facilities for a year and a half. Magnolia Creek was the last facility before she came home. I prayed and prayed she would find success there and it happened. She’s made a full recovery and returned home to us. I can’t say enough good things about Magnolia Creek, and I owe them all the gratitude a parent can give for saving their child’s life.

This kind of transformation doesn’t happen by accident. It requires comprehensive, evidence-based treatment that addresses not just eating behaviors but the underlying body image distortions and mental health concerns that fuel disordered eating.

Find Your Path to Healing at Magnolia Creek

Magnolia Creek provides specialized, evidence-based treatment for eating disorders and body image concerns in adolescents and teens. Our comprehensive approach addresses the physical, emotional, and psychological dimensions of disordered eating and body dissatisfaction, helping young people develop healthier relationships with their bodies and food.

If you’re concerned about your teenager’s body image or eating behaviors, professional guidance can make a critical difference. You are not alone in navigating these challenges. Reach out to our compassionate admissions team today to learn more about our treatment for teens.

References

- Neumark-Sztainer, D., Paxton, S.J., Hannan, P.J., Haines, J., & Story, M. (2006). Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(2), 244-251.

- Puhl, R.M., & Luedicke, J. (2012). Weight-based victimization among adolescents in the school setting: Emotional reactions and coping behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(1), 27-40.

- Paxton, S.J., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Hannan, P.J., & Eisenberg, M.E. (2006). Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(4), 539-549.

- Smolak, L. (2011). Body image development in childhood. In T.F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention (2nd ed., pp. 67-75). Guilford Press.

- Yager, Z., Diedrichs, P.C., Ricciardelli, L.A., & Halliwell, E. (2013). What works in secondary schools? A systematic review of classroom-based body image programs. Body Image, 10(3), 271-281.